In Part I, I traced the journey of indigo from its origins in China and explored the chemistry behind how the pigment was extracted and used to dye materials. In this blog, we delve into how indigo, once a source of pride for India, became one of great suffering, starvation, and revolt for its people under British colonial rule.

In UK schools, we learn of the Battle of Hastings, King Henry VIII and his wives, and the great Industrial Revolution. However, there is little focus on the role of the British Empire in fuelling that industrial growth, particularly its expansion in the 17th and 18th centuries, when it acquired colonies in the Americas, Africa, and Asia.

We are often presented with a single narrative about the Empire that downplays or ignores the global context of history. The interconnectedness of events, particularly how colonialism provided the raw materials and wealth for the Industrial Revolution, is missing from most curricula. In this blog, I aim to provide this broader context by exploring indigo’s history through local, national, and international lenses.

The Role of Colonial Wealth in the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was fuelled by profits from the transatlantic slave trade, sugar plantations in the Caribbean, and other colonial ventures. These profits were often reinvested in industrial infrastructure, banks, and emerging industries. In particular, the growth of the textile trade in Britain was centred around Manchester, a city that became known as “Cottonopolis” due to its booming cotton industry.

While the harsh conditions and child labour in the cotton mills of Manchester are commonly discussed, what is often omitted is the direct connection between the cotton trade and the enslavement of Africans in the Americas, or the exploitation of indigo farmers in India under the British Raj. These stories of exploitation were integral to the success of Britain’s textile industry but are seldom mentioned in traditional accounts of the Industrial Revolution.

The Global Demand for Indigo

Indigo had been in demand in Europe for centuries as a vital dye for textiles. By the 17th century, its vibrant color made it a major commodity in Britain. Originally sourced from Asia, particularly India, the British eventually expanded indigo production to their colonies in the Americas, including plantations in the Caribbean and South Carolina.

In the Caribbean and the American South, indigo was cultivated using enslaved African labor. These regions had no natural history of indigo cultivation; it was introduced by European colonists specifically to meet the growing demand in Europe. The British Empire’s control over these colonies allowed it to import indigo cheaply, maximising profits. Like sugar and tobacco, indigo became a cash crop, cultivated on vast plantations with little regard for the human cost.

India: The Heart of Indigo and Colonial Exploitation

India, however, was different. Indigo was native to India, and it had been cultivated there for centuries. The plant, Indigofera tinctoria, produced the highly sought-after blue dye that had long been used in Indian textiles. But by the 18th and 19th centuries, after the British East India Company had consolidated its control over Bengal, Indian farmers were forced to grow indigo under highly exploitative conditions.

Bengal was especially targeted because of its fertile land, ideal for indigo cultivation. The British planters, backed by the colonial administration, pushed local farmers, or ryots, into cultivating indigo instead of essential food crops. The system of advance payments or dadon trapped farmers in cycles of debt. They were paid paltry sums for their indigo, far below what they needed to survive, and the soil depletion caused by repeated indigo cultivation made it increasingly difficult to grow other crops, like rice, which led to widespread poverty and hunger.

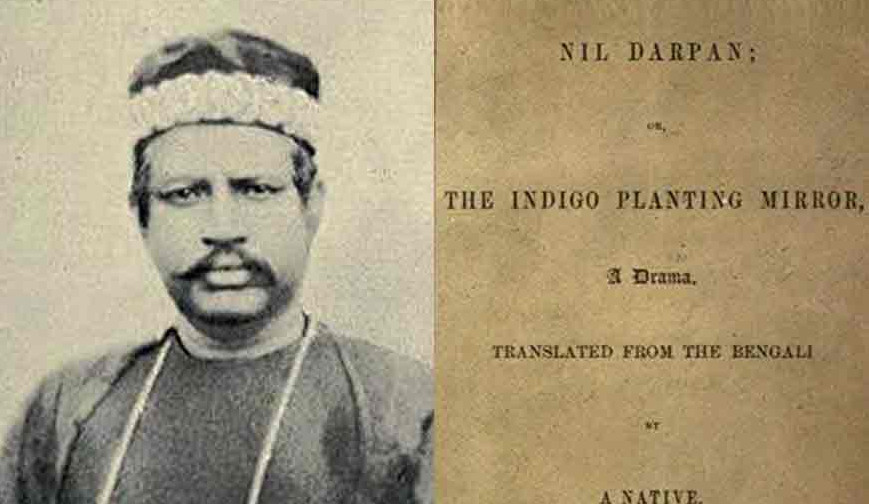

Source: Old Indian Photos.

Causes of the Indigo Revolt

Several factors contributed to the Indigo Revolt of 1859–60, which took place primarily in Bengal:

- Oppressive Conditions: Farmers were forced to grow indigo on a portion of their land, even when it meant sacrificing food crops. The Tinkathia system required farmers to plant indigo on three-twentieths (3/20) of their land, regardless of their needs or preferences.

- Debt and Poverty: The advance payments given to farmers were designed to trap them in debt. The loans, which seemed like financial aid, actually bound the farmers to grow indigo at a loss, deepening their poverty.

- Violence and Coercion: British planters employed private armies to enforce indigo cultivation. Farmers who resisted often faced violence, including beatings and the destruction of their property.

The Revolt: A Turning Point

The Indigo Revolt began in 1859 in the Nadia district of Bengal and quickly spread to other parts of the region. The revolt was marked by non-violent resistance: farmers refused to grow indigo or pay their debts. Leaders like Bishnucharan Biswas and Digambar Biswas organised farmers, uniting them in defiance of the planters.

The British planters responded with violence, burning down villages and attacking the farmers. In some cases, farmers fought back, attacking indigo factories, but the revolt remained largely peaceful. Support from the local zamindars (landlords) helped give legitimacy to the movement, as some landlords sided with the farmers against the British.

Global Context: The West Indies and North America

At the same time, British investors sought to diversify their sources of indigo. They introduced the plant to the West Indies and North America, where it was cultivated largely using enslaved African labour. The British Empire’s control over these colonies allowed it to import large quantities of indigo cheaply, ensuring a steady supply for the textile mills of Manchester and other industrial centers in Britain. This expanded production allowed British manufacturers to produce vast amounts of blue-dyed textiles at low cost, feeding the demand of both European and colonial markets.

Consequences of the Indigo Revolt

The growing unrest in Bengal caught the attention of the British government. In 1860, they formed the Indigo Commission, which confirmed the exploitative nature of the contracts and the widespread abuse of the farmers. As a result, forced indigo cultivation was officially prohibited, though the abuses did not immediately end.

The Indigo Revolt is significant as one of the first major examples of organised peasant resistance in India. It demonstrated the power of collective action and foreshadowed later movements that would challenge British colonial rule. It also had a profound impact on Indian nationalism, as it united farmers, intellectuals, and local leaders in a shared cause.

A Legacy of Exploitation

The story of indigo is one of global exploitation, from the forced labour of enslaved Africans in the West Indies and the American South to the suffering of Indian farmers under British colonial rule. The dye that once symbolised wealth and status in Europe was produced through a system of immense human cost. As we reflect on the legacy of the Industrial Revolution, it is important to remember the untold stories of the people who bore the brunt of that progress.

This is not about making anyone feel guilty. Instead, it is about exploring the truths of our shared past and understanding how interconnected our histories are with the Global Majority—those in Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and the Americas who were affected by colonialism and exploitation. By acknowledging this past, we can better understand how historical forces shaped the present and foster a more honest dialogue about the legacies of colonialism and the inequities that persist today.

Points for reflection

As we reflect on the exploitation of indigo and other colonial resources, it’s crucial to also think about the modern supply chains that bring us the products we use today. Just as colonial economies were built on exploitation, much of today’s global economy still depends on systems that exploit labor and natural resources in ways that are not always visible. Here are some points to consider:

- Do we know where the resources we buy nowadays come from?

- Tin mines: Tin, used in electronics and packaging, is often mined in places where child labour and poor working conditions are still prevalent.

- Cotton: While slavery in the cotton industry was officially abolished, forced labour continues in parts of the world where cotton is grown and processed today.

- Lithium: Essential for batteries in electric vehicles and smartphones, lithium mining often causes environmental degradation and the displacement of local communities.

- What is the compounded effect of a capitalist society on natural resources?

- The drive for profit maximisation has led to the over-extraction of resources like water, timber, and minerals, often at the expense of local communities and ecosystems.

- Water scarcity, deforestation, and pollution are not just environmental issues—they are deeply linked to systems of inequality and exploitation that mirror colonial practices in new forms.

- Reflecting on these points invites us to consider the ways in which our consumption habits are tied to global supply chains and the impact they have on people and the environment, much like the indigo trade was tied to systems of exploitation during the colonial period.

Leave a comment