Recently, I was astounded by traditional Indigo dyeing processes. The process of going from plant to amazing textiles. Since then, I have taken a fascinating deep dive into history. One that starts in China, but then to India and colonial exploitation by the West. In this three-part blog I will share what I have unlearned and relearned. I hope you can join me on this journey to learn more about indigo.

China’s rich and ancient history has always been a source of fascination and pride for many. Growing up as a British-born Chinese, I often found myself caught between two worlds, struggling to understand my place within them. In school, history lessons were overwhelmingly focused on the Industrial Revolution, portraying it as the pinnacle of human achievement led by white British men. This narrow portrayal made it seem as if nothing significant existed before or beyond this period, marginalising other cultures’ contributions. Feeling unseen and disconnected, I began to question and even rebel against my parents’ teachings about the significant contributions of Chinese civilisation. As an adult, I am trying to resolve this internal struggle by delving deeper into my heritage and taking a global perspective on contributions.

When I think of indigo in the West, I conjure up images of blue denim. In the East, it is positively linked to Japanese artistry and history. This further rejects the important global contributions. The history of indigo traditions across various countries is undeniable. This investigation is rooted in understanding my origins, and I am ethnic Chinese. Although indigo has been documented as being widely used in China since the 5th century BCE. India, where the dye takes its name, has been using it since 2000 BCE. In the West, indigo symbolised opulence and was used in everything from fine tapestries to clothes worn by nobility. These richly coloured garments signalled wealth, power, and status.

As a Chemist, I am excited to share the science part. Indigo is a natural dye; its precursor, the active chemical compound, is called indican.

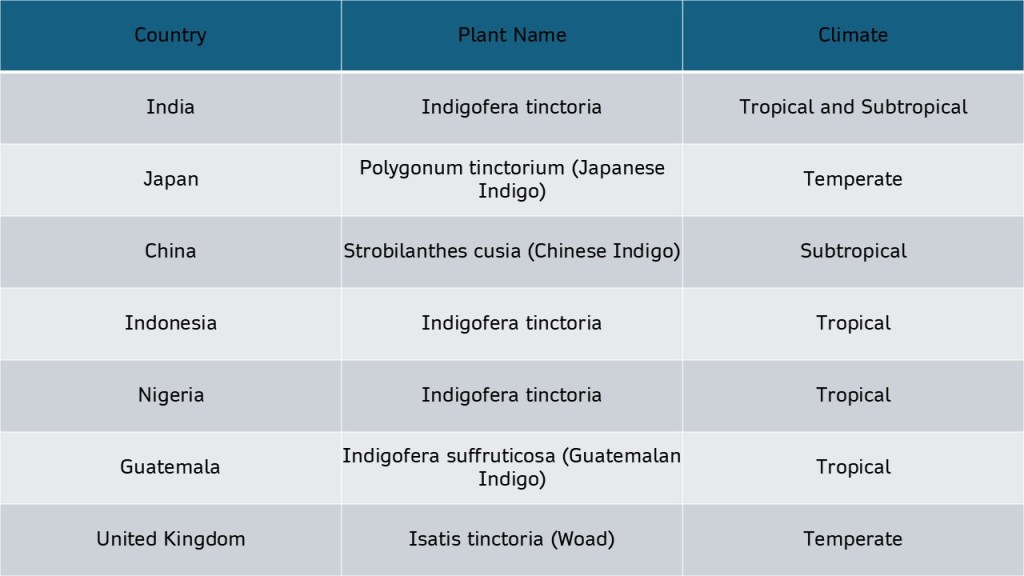

The red in beetroot, betanin, can be found in other vegetables such as Swiss Chard. Similarly, indican is found in more than one type of plant at different concentrations.

Each country has a deep historical connection with indigo. They have developed unique techniques for creating the pigment ‘indigotin’ or ‘indigo‘. It is often also referred to as “Blue Gold.”

Once the leaves are collected, they are soaked and left to ferment. During fermentation, enzymes and bacteria break down the plant cells, releasing indican from the cells and converting it into indoxyl. Workers often stir the mixture to guarantee proper aeration, as this is an aerobic process.

The resulting product is an insoluble blue substance, which settles as a dark blue slurry. This is dried further to form ‘solid indigo cakes,’ ready for use or trade. To dye fabric, reducing agents are added to make the indigo soluble again, producing a greenish liquid. This is where you need to trust the process! The fabric, prepared using techniques like tie-dye or resist dyeing (batik), is soaked in this liquid. The indigo oxidises and turns blue again as the fabric is exposed to air. This process can be repeated to achieve a deeper hue.

Tropical climates are ideal for growing indigo plants in abundance. Yet, each plant produces indigo of varying qualities. The pigment from woad, for example, is less resistant to fading. Indian indigo, however, has long been considered the gold standard—or perhaps I should say, the blue standard. This standard, while highly prized, ultimately contributed to the downfall of the Indian people under British rule, a story I will explore further in the next blog.

Credits: Featured image

Leave a comment